In the late 1990’s the Project LAG in Nara started a sensibilisation programme to fight against the practice of female circumcision in the villages of our intervention zone (commonly called FGM Female Genital Mutilation in the Western world).

It was a daring undertaking, that had the potential to ruin the success of the project in no time and make us loose all the trust from the inhabitants of the villages, that we had gained over the years. Trust and cooperation are the essential ingredients to make a development project work. Many heated discussions, if we should or should not engage openly in such an activity, had taken place before. Female circumcision is a religious, cultural and symbolic concept and its practice has its origin thousands of years back.

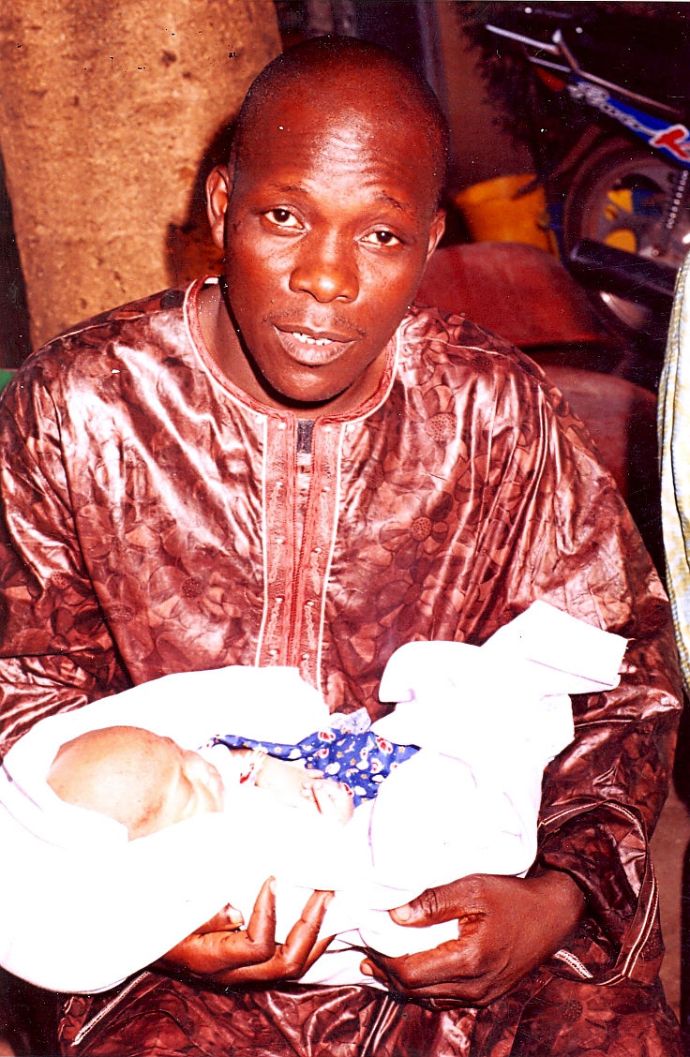

On the field-level and grass-root level Fatoumata Couliably and myself were responsible for the implementation of this programme. But the whole team was involved in developing a strategy for this complex and delicate topic. I could write an entire book about what I learned and heard from Fatime and the women in the villages concerning the practice of female circumcision. I could write an entire book about the emotions, the fear, the pain and the pride as well, that many women surprisingly still felt instead of all the hardship they had been put through by their mothers and grandmothers.

” The problem will be,” said Cheik Camara, the eldest and wisest of the team members, ” to convince the mothers. It is much more difficult to convince the women to give it up than the men. It has nothing to do with Islam either. It is much deeper”.

I could tell so many intimiate, moving and emotional stories of circumcised and excised Malian women and girls. And I will come to that point, but however today I have compiled a ” more scientific summary” to enable readers to first understand the history, the symbolism, the different practices and the health consequences surrounding FGM because it is no ” easy” concept at all.

Over 90% of the women in Mali are still being circumcised or excised today.

FGM is considered by its practitioners to be an essential part of raising a girl properly—girls are regarded as having been cleansed by the remove of all “male” body parts. It ensures pre-marital virginity and inhibits extra-marital sex, because it reduces women’s libido. Women fear the pain of re-opening the vagina, and are afraid of being discovered if it is opened illicitly

Definition: Female Circumcision or Female Genital Mutialtion (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”

The word “mutilation” differentiates the procedure from male circumcision and stresses its severity

The WHO has offered four classifications of FGM. They are classified as follows:

Type I, removal of the clitoral hood, almost invariably accompanied by removal of the clitoris itself (clitoridectomy)

Type II, removal of the clitoris and inner labia. This type of FGM is also often called excision in West- Africa.

Type III (infibulation), removal of all or part of the inner and outer labia, and usually the clitoris, and the fusion of the wound, leaving a small hole for the passage of urine and menstrual blood—the fused wound is opened for intercourse and childbirth. Type III, commonly called infibulation or pharaonic circumcision, is the removal of all external genitalia. The inner and outer labia are cut away, with or without excision of the clitoris. The girl’s legs are then tied together from the the hip to ankle for up to 40 days to allow the wound to heal. The immobility causes the labial tissue to bond, forming a wall of flesh and skin across the entire vulva, apart from a hole the size of a matchstick for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, which is created by inserting a twig or rock salt into the wound. There is another form of Type III called matwasat, where the stitching of the vulva is less extreme and the hole left is bigger.

In Type 3 excision or infibulation elderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the lithotomy position. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the fourchette, and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora.

Bleeding is profuse, but is usually controlled by the application of various poultices, the threading of the edges of the skin with thorns, or clasping them between the edges of a split cane. A piece of twig is inserted between the edges of the skin to ensure a patent foramen for urinary and menstrual flow. The lower limbs are then bound together for 2–6 weeks to promote haemostatis and encourage union of the two sides. Healing takes place by primary intention, and, as a result, the introitus is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture.

Around 85 percent of women who undergo FGM experience Types I and II, and 15 percent Type III.

Type III is the most common procedure in several countries, including Sudan, Somalia, and Djibouti. Several miscellaneous acts are categorized as Type IV. These range from a symbolic pricking or piercing of the clitoris or labia, to cauterization of the clitoris, cutting into the vagina to widen it (gishiri cutting), and introducing corrosive substances to tighten it.

FGM is typically carried out on girls from a few days old to puberty. It may take place in a hospital, but is usually performed, without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser using a knife, razor, or scissors. According to the WHO, it is practiced in 28 countries in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, in parts of the Middle East, and within some immigrant communities in Europe, North America, and Australasia.

The WHO estimates that 100–140 million women and girls around the world have experienced the procedure, including 92 million in Africa. The practise is carried out by some communities who believe it reduces a woman’s libido.

The vulva is cut open for sexual intercourse and childbirth. In some communities, when a pregnant woman who has not experienced FGM goes into labour, the procedure is performed before she gives birth, because it is believed the baby may be stillborn if it touches her clitoris. The risk of haemorrhage and death from FGM during labour is high.

During three six-month studies in the 1980s, Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed 300 Sudanese women and 100 Sudanese men, and described the penetration by the men of their wives’ infibulation:

“The penetration of the bride’s infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man’s potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman’s vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. A great deal of marital anal intercourse takes place in cases where the wife can not be penetrated—quite logically in a culture where homosexual anal intercourse is a commonly accepted premarital recourse among men—but this is not readily discussed. Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the “little knife.” This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis. In some women, the scar tissue is so hardened and overgrown with keloidal formations that it can only be cut with very strong surgical scissors, as is reported by doctors who relate cases where they broke scalpelsin the attempt.”

The term “pharaonic circumcision” stems from its practice in Ancient Egypt under the rule of the Pharaohs.”Fibula” (in “infibulation”) refers to the Romanpractice of piercing the outer labia with a fibula or brooch. Genitally-mutilated females have been found among Egyptia mummies.

It is said as well that the common attribution of the procedure to Islam is unfair because it is a much older phenomenon.

What has been summarised and said about FGM in this post is compatible with my findings and experience from the encounters I had with the girls and women from our project zone.

I have written this post today because my friend and old collegue Cheik Fadel has send me a website link two weeks ago. I am very pleased to see that the awareness what FGM is, is growing and that more and more women and men are joining the activismn against its practice.

Here is another wordpres site about female excision that you can follow

http://marcheencorps.wordpress.com/lexcision/